Notes & Thoughts

Science fiction often takes the same form as ordinary fiction. That is to say, it has characters and a plot. What marks it out as science fiction will be something that has been changed in the fundamental structure of the fictional world, compared to our real world. The author will then play a story out, and we will see how ideas, concepts, people and society, are changed due to the environmental differences.

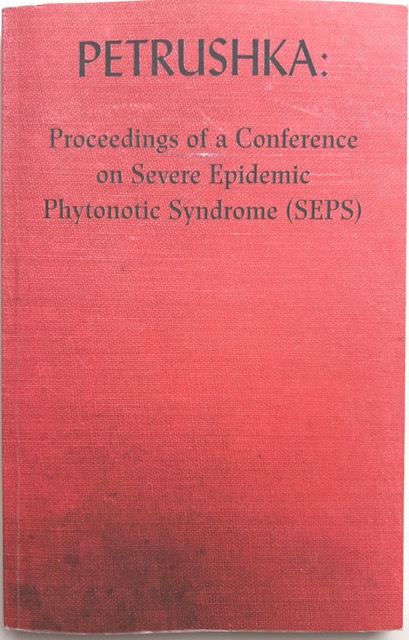

In the case of Petrushka, which takes the form of the proceedings of a conference, the author dispenses with a plot and characters (to some degree) and can simply focus on exploring the modified ideas and concepts necessary in the new environment. Thus he avoids the potential awkwardness that can occur when trying to explain ideas through the story and characters. The awkwardness comes from making the characters over-explain just for the reader’s benefit and thus behaving in a way that they wouldn’t if the reader were not watching (or reading). Or forcing explanations into the narrative at the expense of the plot. Free of characters and plot, the author can simply lay out ideas and concepts more or less directly. Thus, I think, he is able to explore more ideas; and it all feels quite natural. The downside with this approach is that you wouldn’t be able to use it more than once. It works because of it's novelty.

As it happens, at the same time as I read this book, I was also reading Ian McEwans latest novel What we can Know. It's perhaps not strictly speaking science fiction, but part of the novel is set one hundred years in the future after climate change has wreaked havoc. (Science prediction fiction?) He does have his characters talk about climate change and some of the events it has caused, and (I think) it did seem somewhat unnatural. This is from an author who is a master craftsman of plot and character.

It did occur to me while reading the book that if you were to set out to write a science fiction book, you might start by brainstorming all of the ways in which society might alter as a result of your fundamental change in your fictional world. And the result might look something like this book. Notwithstanding the fact that in this case there is the proceedings of a conference structure. Although, even that is quite loosely applied.

The book notes an interesting phenomenon. That sometimes, large scale crises can have benefits for some people. “The bubonic plague of 1346-1353 is estimated to have killed between 75 and 200 million people, between 30% and 60% of Europe's population. ... People who survived benefited. Workers wages rose. Feudal institutions crumbled with the demand for wage labour.” Page 109. I recently watched an interview of Luke Kemp1, author of the book Goliath's Curse (which I'm considering reading) which is about societal collapse and he made a similar point about beneficial outcomes of collapse for some. He points out that the average height of people (which is quite a good general marker of well-being since it depends on access to resources, e.g., good food) went down when countries were conquered by the Roman Empire, and then back up when the Roman Empire collapsed.

“People have to learn how to critically read newspapers and watch TV (assuming it survives). There are courses aimed at sharpening critical thinking on where and how to look for things. There will have to be renewed investment in civic education to teach people how to identify and value the truth, and how to identify a hoax.” (Page 115). Definitely something that occurs to me often these days as social media algorithms and AI further diminish the practice of critical thought. Also, the attack on language and reason waged by the far right demagogues which gets a chapter in Ece Temelkuran's book How to Lose a Country which I read recently2.

“In urban societies, people are spending 90% of their time in-doors. We have effectively disconnected from nature. To keep us connected and healthy, both mentally and physically, humans need to think about the need for nature and integrate this need into our way of life.” (Page 119). This resonates. My photography outings are increasingly to places of nature. And my reasons for doing so are primarily to be in nature. I'm typically drawn to urban photography. But I've been learning to take photos in nature because that is where I need to be sometimes. In my case this is often Walthamstow Marshes, which I can get to in about fifteen minutes on the bike.

STOP PRESS. I've been on the internet. It tells me that there was in fact a conference on which this book was based. "In 2016, he [Peter McCarey] convened and chaired a meeting of international experts on an ‘impossible pandemic’. The proceedings were published under the title Petrushka, 2017". Unfortunately I can't find anything else on the internet about this conference. I was hoping for some footage on Youtube.

There is very little about Peter McCarey online. His brief bio on the Scottish Poetry Library says "Peter McCarey was born in Paisley and brought up in Glasgow, before studying and working in Europe, Africa and Asia; he lives in Geneva. He graduated from Oxford with a degree in Russian and French, and has a PhD from Glasgow University in Russian and Scottish literature. He has worked as a freelance translator, and for many years as Head of Language Services for the World Health Organisation."

Also by Peter McCarey is this extraordinary feat of poetry. The Syllabary. The Syllabary consists of 1319 empty sounds and 2281 spoken parts of 1 to 37 lines in length, each based on a cluster of between 1 and 47 monosyllabic words. The program chooses an ititial text at random and leads the viewer to the next in any of three directions through some 15013 lines of verse. This is the sort of thing the www was invented for.

1. Bad Idea #23 "These are the best of times" with Luke Kemp

2. Notes and Thoughts on How to Lose a Country